Recently, I've decided to start rereading some of my linguistics textbooks to brush up on and maintain my knowledge and skills. Yes, I know, I'm a nerd. But you're reading this blog, so really, who's to say? I kid.

I'm starting with the textbook for my introductory linguistics class, which was Linguistics For Everyone. I honestly loved this textbook and recommend it to everyone who's interested in linguistics. After reading through the first chapter, I started to look over the review section. The first review exercise asked one to think about the connection between onomatopoeia and arbitrariness, one of the design features of language.

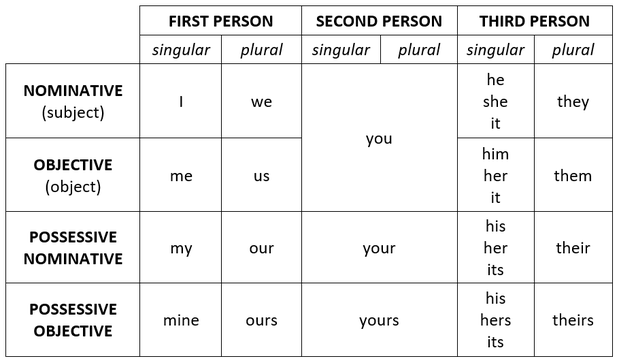

Charles Hockett introduced six design features of language that characterize human language and separate it from other communication systems. (There are like ten more that he later came up with, but the book focuses on these six, so we'll go with these.) They are as follows:

- Semanticity - all signals must have meaning

- Arbitrariness - there is no logical connection between the signal and the idea it represents

- Discreteness - any message can be broken into parts (e.g., sentences into words, words into sounds)

- Displacement - the language user can discuss things that are not present (either physically or chronologically); this also includes abstraction, talking about things that are not tangible (such as ideas)

- Productivity (or generativity) - language users can understand and create completely new utterances

- Duality of patterning - a number of meaningful utterances can be recombined in a systematic way (such as prefixes can be combined to various root words).

Other communication systems (animal languages, traffic signs, etc.) can have some of these design features, but only human language has all of them. It's the difference between communication and true language.

So, as said earlier and as this post is titled, the review exercise asked us to think about the connection between onomatopoeia and arbitrariness. Apparently, this is quite the topic for debate among linguists. Well, here are my thoughts.

Onomatopoeia is a word that represents a sound, such as bam or buzz. Is the connection between woof and the sound a dog makes arbitrary or not? Well, it's not black and white, but I argue that it is arbitrary.

Arbitrariness is proven by different words for the same concept across various languages. There's no logical reason that a dog is called a dog in English or a perro in Spanish or a собака in Russian. Similarly, there's no logical reason that a rooster should say cock-a-doodle-doo in English but cucurucu in Portuguese. As my first linguistics professor said, the rooster doesn't actually sound different in Portugal or anywhere else; the onomatopoeia is arbitrary.

Of course, there are similarities in onomatopoeia across the languages (rooster calls all seem to have a repetitive [k] sound and four or more syllables; check out this cool webpage that lists a bunch of other languages' versions), while dog and perro and собака couldn't be more different from each other.

This is because there is a somewhat logical connection between the signal (cock-a-doodle-doo) and its concept (the sound a rooster makes). Onomatopoeic words are trying to be representative or iconic of the sound it's signifying, so it's not completely random or arbitrary. That would mean that my argument for onomatopoeia being arbitrary is false. But! I have a counterargument.

The textbook also brings up sign languages in relation to Hockett's six design features and discusses how sign languages are also full human languages that fit all six features. I minored in American Sign Language and highly enjoyed this recognition of sign languages as valid. (Did you know that ASL was only recognized as an official language in the 60's? A discussion for another time.)

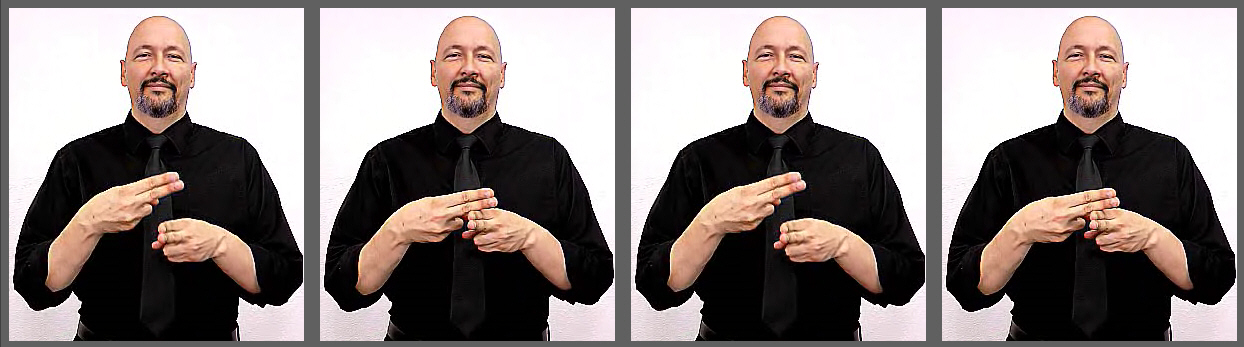

In terms of arbitrariness, many signs do not have a logical connection between the sign and the concept. For instance, the sign for name:

Or the sign for trash.

Or the sign for trash.

However, there are also many signs that are iconic, or there is a logical connection between the sign and the concept. For example, the sign for cat:

As you can see, the sign makes a motion like pinching a whisker, which cats have. Another example is the ASL alphabet. Practically all of the letters are iconic of the English alphabet, such as the sign for C, in which the user curves their thumb and fingers to make a c-shape.

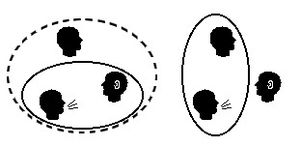

Despite these rather non-arbitrary iconic signs, ASL still has the quality of arbitrariness. In fact, even for these iconic signs, there is variation across sign languages. Below is a comparison between the signs for cat in American Sign Language and British Sign Language.

The BSL sign also represents whiskers, funnily enough, but it uses two hands and all fingers to demonstrate the whiskers. This represents a similar kind of arbitrariness that onomatopoeia displayed across languages.

In the first chapter of Linguistics For Everyone, the book states that there is a "language-dialect continuum" that all varieties of language fall on. I assert that all words fall somewhere on an arbitrary-iconic continuum.

I argue that, even though there is a logical connection between the onomatopoeic word and the sound it represents, because the words vary over languages and there is no logical argument for one language's onomatopoeic word over another's, that onomatopoeia still has the quality of arbitrariness.

What does a rooster say where you live?